|

|

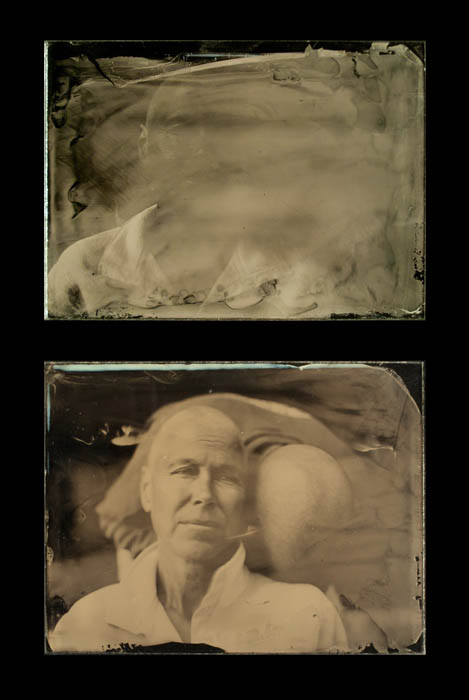

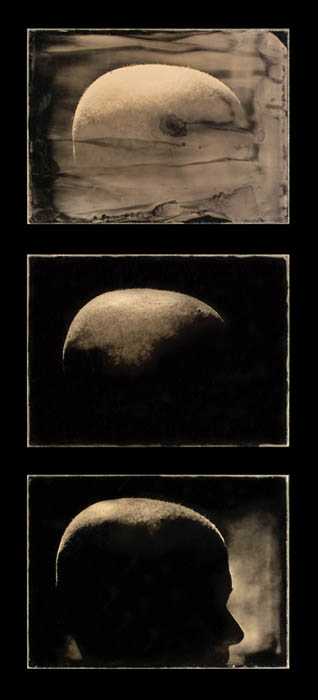

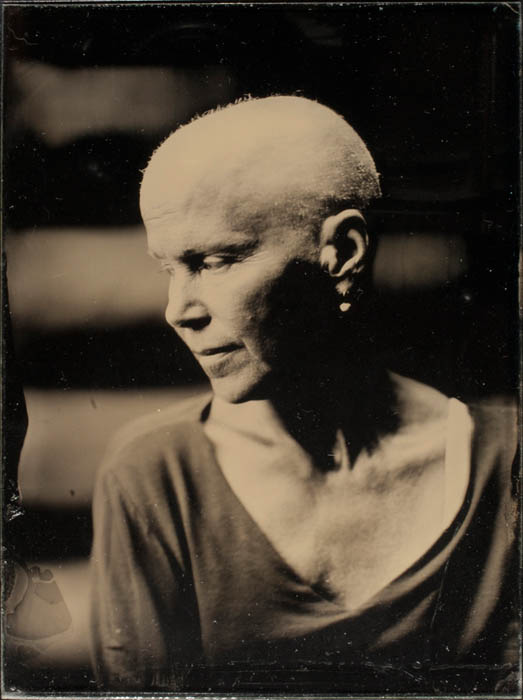

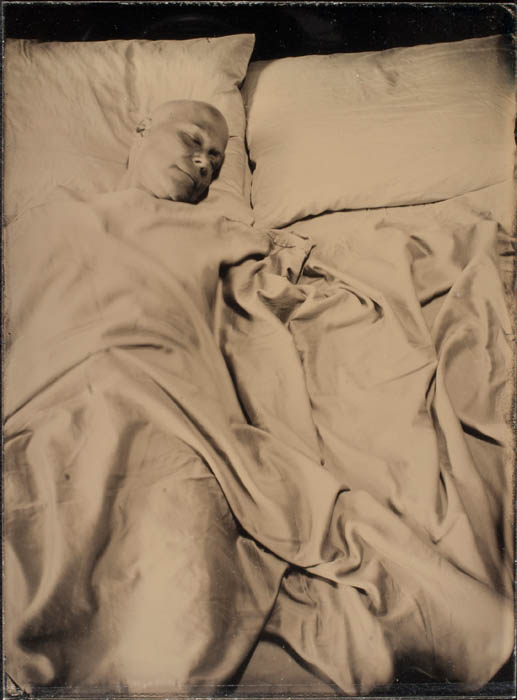

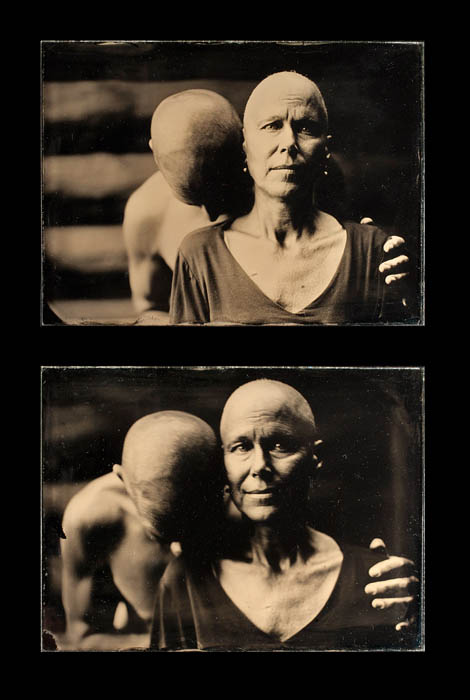

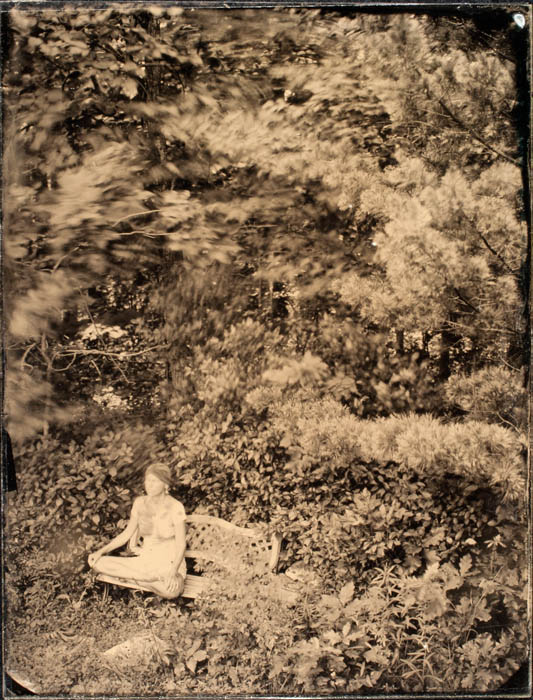

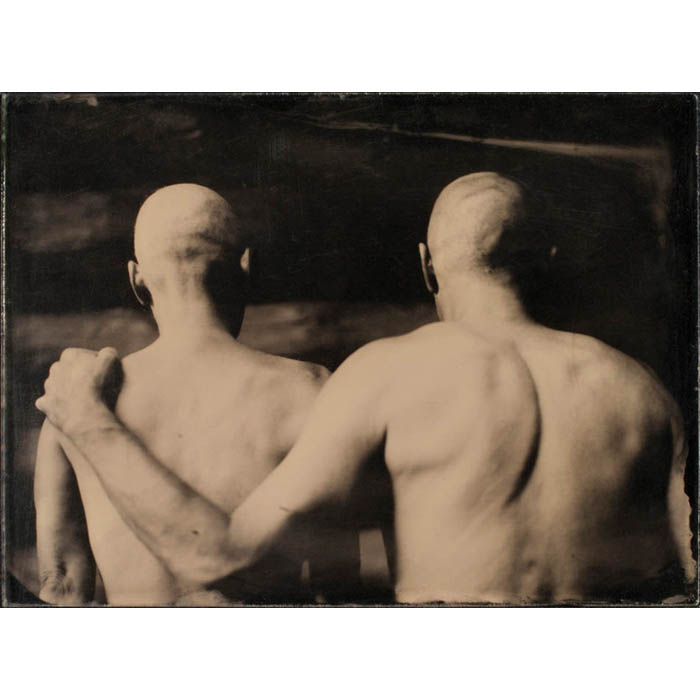

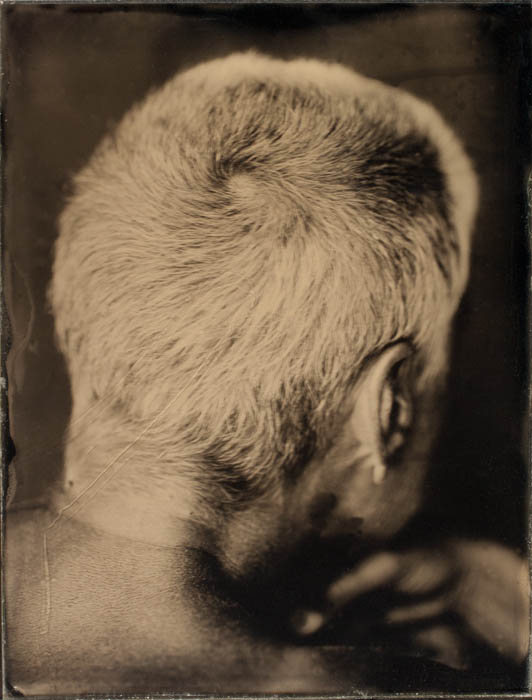

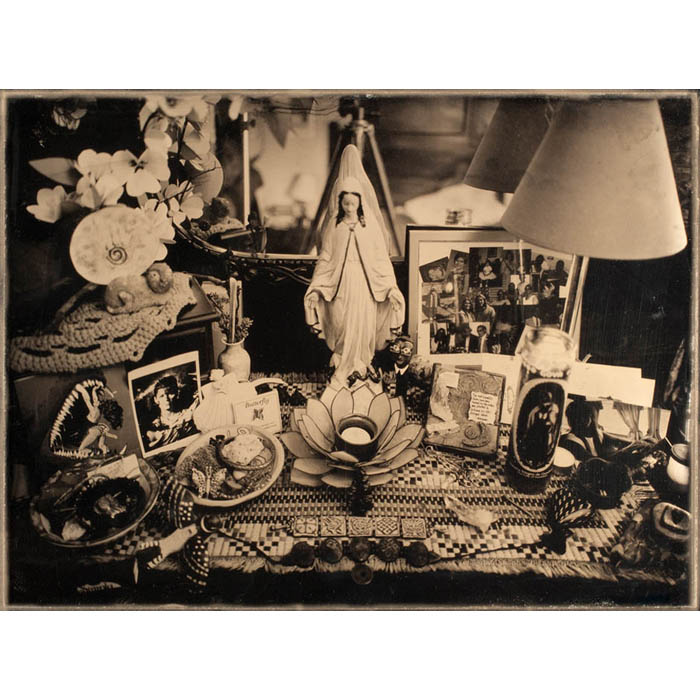

Chemo Toxic Just six days after returning from a Fulbright in Croatia I drove my wife Michele to the emergency room due to stomach pains. A CAT scan revealed a grapefruit-sized tumor on her left ovary. She underwent emergency surgery the next day. With the realization that she had cancer our lives changed in an instant. There was no way to make sense of the diagnosis, as she is one of the healthiest persons I have ever met. On that memorable day (February 14, 2010) I found myself unable to make sense of it and quickly realized that I needed to look forward and not try to reason why. I am always photographing and recording the details of my life. I have been doing this for almost 4 decades. It is second nature to me. When this happened it was the first time in my life that I was unable to record the events around me, as I just wanted it to go away. I wanted no record. I froze. It wasn’t until after the hopeful pathology report that I was able to begin to consider documenting as we began to rebuild our lives. Learning this photographic technique became my “therapy” while coping with the changes we faced. A parallel process occurred. I was learning about cancer while learning about the Wet Plate Collodion Process. An amazing metaphor evolved as I realized that the quality of the work improved as Michele’s health improved. She began Chemotherapy on March 30th. I spent the spring of 2010, the second half of my sabbatical, caretaking Michele and making images. I was learning how to use this complicated and sometimes frustrating photochemical process, as she underwent her own ‘chemical process’ of Taxol and Carboplatin. Chemo Toxic is the term used to describe the impact of chemotherapy on the body, specifically 48-72 hours after getting dosed. Toxic waste products are present in body (urine, stool, saliva, secretions). The patient is told not to exchange body fluids with others, nor let children or pets play near the patient’s toilet. When I heard this term, it kept resounding in my head. In essence, the body is being poisoned with the intention of killing the fast-growing cancer cells. The Collodion Process is an antiquated technique developed in the 1850s. The chemicals used include silver nitrate, nitric acid, cadmium bromide, grain alcohol, lavender oil, and potassium cyanide among others. The result is a one-of-a-kind image printed on a glass plate known as an Ambrotype. I believe the images reflect fear, hope, hard work, beauty and transformation. This is an ongoing body of work and the exhibition currently includes 27 images in 21 frames. Individual image sizes are approximately 5x7 inches. The frames for single images are 16x20 inches in black wooden frames. There is also a group of approximately 10 formal Ambrotype portraits made throughout the Chemo Therapy process that are approximately 8x11 inches.

Radio InterviewInterview with Hugh Grant of FotosavantWhat was your previous experience/knowledge of Ambrotype before ChemoToxic began? I was interested in the Ambrotype process before this series came about. I actually was on sabbatical and had just finished a Fulbright Grant in Croatia and came home for a few months before going to South Korea for a photographic commission and just a few days after returning from Croatia Michele was diagnosed. One of my plans for the sabbatical (if the other proposals failed) was to learn the process as I’ve always had an interest in it and some photographic ideas of how to use it. When the diagnosis was revealed it was the first time in my life that I did not want to record it; I just wanted it to be over and gone. After a bit of time and a fairly optimistic diagnosis my need to document began to grow and I thought of the wet Collodion process. As my artists’ statement says: Learning this photographic technique became my “therapy” while coping with the changes we faced. A parallel process occurred. I was learning about cancer while learning about the Wet Plate Collodion Process. An amazing metaphor evolved as I realized that the quality of the work improved as Michele’s health improved. So, thus began my experimentation with ambrotypes (and psychological diversion away from cancer). At a time (of emotional challenge, fear and/or confusion) when others might turn to a familiar medium for comfort or distraction, what led you to confront the challenges and frustrations of a new process? Diversion, as stated above. I love to work with my hands and while I am fluent with the computer I honestly get sick of sitting in front of the screen. My research, class prep, grading, correspondence, and more all deal with the use of the computer and my creative work has always been separate from all of that. It has always been a meditation and therapy for me. I teach at RIT and there is such pressure to ditch all the analog classes. It seems I’m about the only one wanting to keep it alive. Another intent (that I did not mention above) is that I hope to create an Ambrotype class to teach at RIT where there is plenty of interest from the students. Was there a vision of the arc or purpose of the project from the beginning or did it emerge? When I start a visual project I never know what will emerge. If I did then it becomes too mechanical and that is a bore. That is what is so refreshing about creativity. I start because I don’t understand something or have questions. In this case I needed a diversion and was wondering how my camera and this process would see what is going on and how that would resonate with my emotions about what Michele was going through. Photography is a tool that shows you what is there in front of you. I’m not interested in reality or what is there; I’m interested in what else is there. That is what artists do. When I began to see the results of this photochemical process we began to see the results of the chemo process. Together they both started to work and the healing began for both of us. My artwork is therapy. I do it for me. If others don’t like it that is okay, I have to make it for myself and then look at it and see what it has to teach me. I have students who graduate and feel the loss of the community and the critique and my advise to them is to make work, work hard and then spend time with it and see what it has to teach you. My work is my best teacher! You seemed very clear in making the battle against disease one in which you were a participant, not merely a spectator. The visible evidence of Michele's battle is in the plates, how does your battle manifest itself in ChemoToxic? My battle manifests itself by making the plates. Yes, Michele’s battle is seen in the plates and would not be there (emotionally and beyond the chemical action) if it were not for my passion for her and making images and her patience by being willing to sit still for 60 or so seconds for each exposure. For me to make each image it basically takes a full day between testing, learning and redoing and finishing the plates. Her patience was amazing and courage tremendous while going through the chemotherapy process. When I asked her if she would be willing to sit for these portraits she felt compelled because she was curious to see how the camera would record her during this evolution in our relationship. Does the physicality of the glass plates figure in to the presentation of this series? (In what way might those who only get to see it in print or online lose a dimension of the message? If at all?) The Internet is pretty good for showing a facsimile of the object, but it is not the real thing. What I like about the way I am using this process is that there is only one original glass positive and no negative. These are all in-camera originals. This process can make negatives and copy positives made from that but I specifically wanted (in this digital world of reproduction) to have only one original. I love that idea! They are not for sale, I’m not interested in that and fortunately I don’t have to support myself from my art because my work at the university does that. I feel that when one has to do live off of selling their art, to a certain degree, you have to make compromises for the sale and then the work is not true to you in the same way. I know many will disagree with this but it is what I have found. So, I feel that looking at the work on line or in print form is not the original but the viewer can still get a very good sense of the emotion conveyed in the piece. I’ve been a fan of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel for decades and wrote a major research paper on it in college and felt I knew it very well but when I finally got to Rome and stood there looking up at it I had a minor incident of Stendahl’s Syndrome and realized that I really did not know the piece at all. For me there is something much more immediate about the original one of a kind that shows the marks made by the hands of the artist that you don’t quite get by looking at it online. In the digital world we have 100% reproduction quality from a digital negative. To a certain degree there is a loss of the individuality of the piece due to the digital reproduction. I am not saying one is better or worse, just different. Was there ever a point in shooting some of the images that Michele wanted to (or did) say, "I don't want to pose." and/or "Just let me be sick and give the camera a rest?" No she never did say that. However, before the sessions I did check in with her to see about her energy level. These sessions took several hours. I would have to coat the plate, sensitize it, make the exposure, develop and evaluate it before making another one. Often we would make several plates of each sitting which could take several hours. We would only do one image per day and at most 2-3 times a week, except after her Chemo treatments when she was wiped out for most of the week or more. Any specific plans for further exhibition and/or publication? Yes there is a major exhibition planned for this spring at the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester that opens on May 3. It will not only have the images of Michele but also a new project that I am currently working on called I Am That. It is a series of self-portraits using the 11x14 camera that has been inspired by a book of the same name by Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj. It is a book of his teaching about the image of self and what it means. As means of description one of the quotes reads: Once you know that death happens to the body and not to you, you just watch your body falling off like a discarded garment. I have spent time seriously investigating the afterlife and spirituality and the power of thought but not to the point where it takes over. What this book teaches me is that how we perceive our body and selves is transitory. I began to wonder, based on what Michele went through, if I may have some festering cancer in my body that will take over and consume me and push me though a similar type of chemical therapy that so many go through. For this part of the exhibition I did not want to just have the Ambrotype plates framed on the wall similar to the images of Michele. In my research about the contemporary use of the Ambrotype there are many who are making timeless images that for me mirror too much of the old days. For this body of work I want to literally look inside (or more specifically look through) my body to see what I (metaphorically) have. I don't know if this makes sense or not so let me describe what the presentation will look like. I am creating a sculpture that will have about 50 11x14 plates suspended by wired that abstractly represent my body. The wonderful thing about Ambrotypes is that they are transparent/translucent and when you view them against a black surface they will be positive images and when you view them against a white surface they will be negative images. This opens up a lot of interpretation and ambiguity which is what we all seem to face as we age and our minds feel like they are still in their twenties but the bodies don't necessarily agree. My visualization is that these floating sheets of glass will be arranged in a way so that as one moves around the sculpture, the complexity of images overlapping will create unlimited views. The final size will be about eight or ten feet high and about five feet wide in places and the plates will float in the gallery. Currently I am making a small model to work out the organization of the plates. Another aspect of the exhibition is to have a fundraiser primarily for the Pluta Cancer Center, where Michele received her treatment as well as for Visual Studies Workshop. The staff at Pluta Cancer Center shows so much compassion for the patients that we really want to give back and support their efforts. As an example when we first went to meet with them to discuss the treatments our oncologist spent an hour and a half with us going through the process and answering all of our questions and explaining what would happen. An hour and a half! We found this amazing in this day and age of 10-minute medical treatment slots. There are many other examples I could list but will only say that the compassion shown by all the staff is what it should really be about and my theory is that if an organization has that attitude it has an affect on the patients outcome (now we are back to Nisargadatta's teachings). One way to raise funds for the cancer center is to have a Shave Your Head For Cancer event the evening of the opening. I have long been aware of people getting sponsors for running a race to raise funds and I thought it would be courageous for some (myself included) to raise funds to have their heads shaved and the monies go to the cancer center. For all of those that do I want to make an Ambrotype portrait of them for my next project. Other activities will include commissioned portraits and print sales. As for further exhibitions/publications once this exhibition is opened in May I hope to travel it and have already been approached by a publisher. These projects take time and money and, as always, I am very hopeful. Any particular reactions from cancer patients or their families upon viewing the work? Yes there has been quite a bit. Yesterday I received a call from a woman who has breast cancer and is using photography to document her journey. She is volunteering at Pluta Cancer Center. From the exhibition in North Carolina I have networked with several who are dealing with cancer and doing the same in a variety of mediums. It is art therapy and it helps us to accept the situation. In the future I would like to research and curate a major exhibition that deals with these issues as so many could benefit. I'd be seriously remiss if I didn't ask one last question; how is Michele doing these days? Michele will be 3 years out (as they say) next month on February 14. Every 4 months we have a terrifying meeting with the oncologist that is preceded with blood tests that show how her numbers are doing. For the week before we live on edge as all could change depending on the numbers. So far all the numbers have been great and she continues to improve. Chemo is a funny drug as it gets into your system and, as I say, sort of kills you, or kills the quickly reproducing cells such as cancer, hair, stomach lining and others. As a result she will never be quite the same as before the chemo and while the changes are relatively small it is still a change. Different people are affected differently by it and fortunately here changes are small. |